At the heart of US policy is a fear of the world growing beyond it. However, despite its efforts it has been unable to prevent it. This is the cause of many of the world’s problems now and the US’ use of the dollar as a weapon to prevent growth is driving a move away from the dollar in the 21st Century.

Prior to the Great Financial Crisis, IMF and World Bank loan portfolios were already shrinking but the shift away from the dollar has greatly accelerated in recent weeks with China, Russia, India, Saudi Arabia, Kenya, Indonesia and Brazil, among others, all taking steps to insulate themselves against the iniquities of the USD to greater or lesser extents.

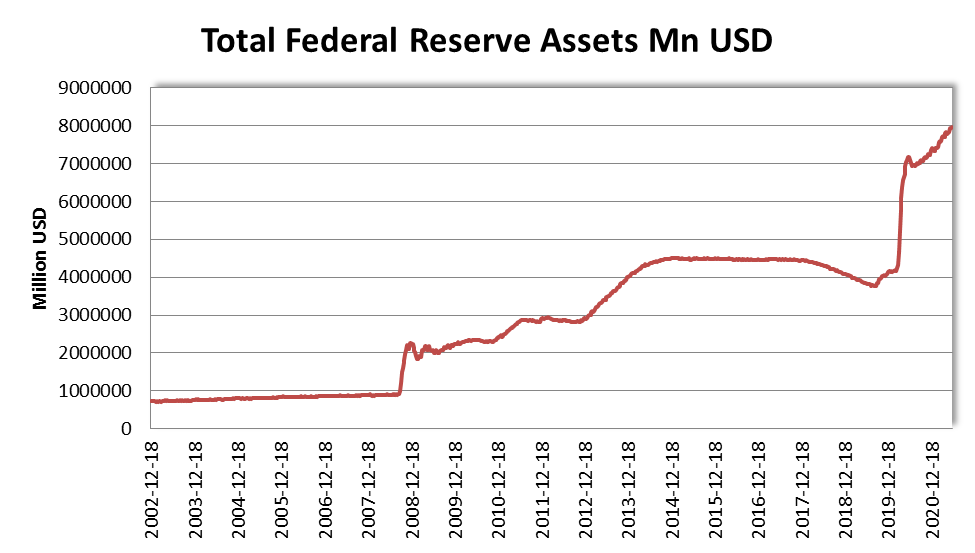

At the end of the Second World War the United States was the world’s largest industrial economy, largest creditor nation and held over sixty percent of the world’s gold reserves. Developed economies linked their exchange rates to the USD and the USD was linked to gold. This ended in 1971 when President Nixon was forced to suspend the Dollar’s convertibility to gold due to massive military spending in Southeast Asia that French banks recycled into gold at the Fed. This became known as the “Gold Window.”

By closing the Gold Window, the USD became the world’s first fiat reserve currency – meaning it was effectively backed by nothing. However, a subsequent deal with Saudi Arabia and OPEC allowed the USD to retain its reserve status.

The Reagan years further undermined the rationale for the dollar’s reserve status by transforming the US from an industrial to a financial economy, undermined the competitiveness of US production and facilitating outsourcing of productive capacity to the developing world taking advantage of lower wage costs.

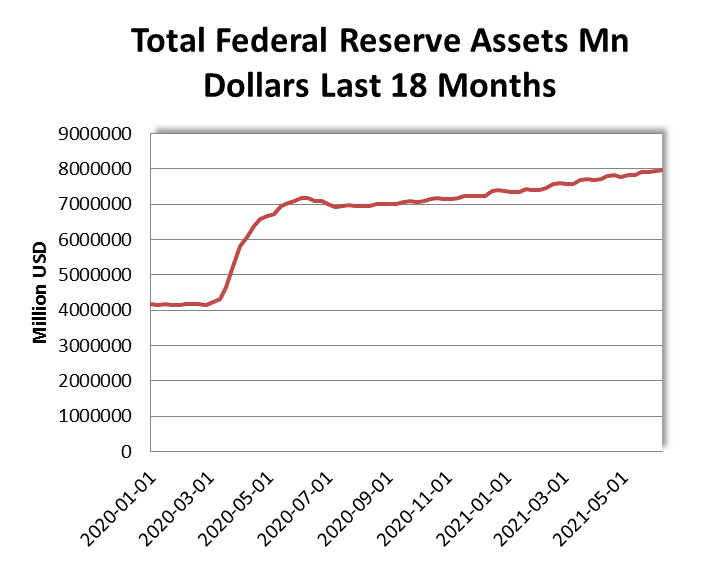

As US trade deficits grew and military spending abroad ballooned, countries were forced to exchange vast piles of dollars for treasury bonds – effectively lending the money back to the US at negative real interest rates. Through economic sanctions and central reserve seizures the US has sought to weaponize the USD to punish those that dissent against the neo-liberal hegemony of Washington.

As it becomes obvious the US has no intention – or means – of ever repaying its debts, countries have been forced to ask: what’s the role of the US in their international transactions? Unfortunately, the answer increasingly looks like a protection racket. Ensuring your leaders don’t get assassinated, your government doesn’t get ‘regime changed’ and your country doesn’t get bombed.

With this in mind, countries across the world are taking steps to insulate themselves from the potential weaponization of US dollar by shifting bilateral trade to either local or powerful third currencies like the Chinese RMB.

De-dollarization of the global economy is not a process that can happen overnight because the USD is heavily entrenched and still carries many benefits. As Yves Smith of Naked Capitalism points out, in many ways and for many people it’s still the cleanest shirt in the laundry.

Moving central bank reserves out of USD will take time and needs planning as well as structural adjustments within alternative currencies but will ultimately happen. Ironically for the RMB, China’s inability to generate the massive current account deficits necessary to absorb foreign accumulations of Chinese currency will slow this process.

It is also worth remembering that it took two world wars and a Great Depression to end the reign of the Pound Sterling as the global reserve and the USD is more entrenched. But in the digital age things can happen fast and global opinion is shifting quickly as the US becomes more unpredictable and mercurial.