A version of this article originally appeared in Beijing Review.

Horgas Dry Port

Xinjiang, an autonomous region in northwest China, is home to vast deserts and mountains and many ethnic minority groups. The ancient Silk Road trade route linking China and the Middle East once passed through Xinjiang, and its legacy can still be seen everywhere. The dry port Horgas is breathing new life into this ancient trade route.

Horgas, once a sleepy backwater straddling the border of Xinjiang’s Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture and Kazakhstan has been transformed as a key part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Its strategic position has turned the city into the one of the largest dry ports in the world and the starting point for the China-Europe railway. And the demand is growing.

Thanks to the dry port, trains and trucks can carry goods from eastern China to Western Europe in around two weeks, compared to a several week journey by container ship or vastly expensive air freight.

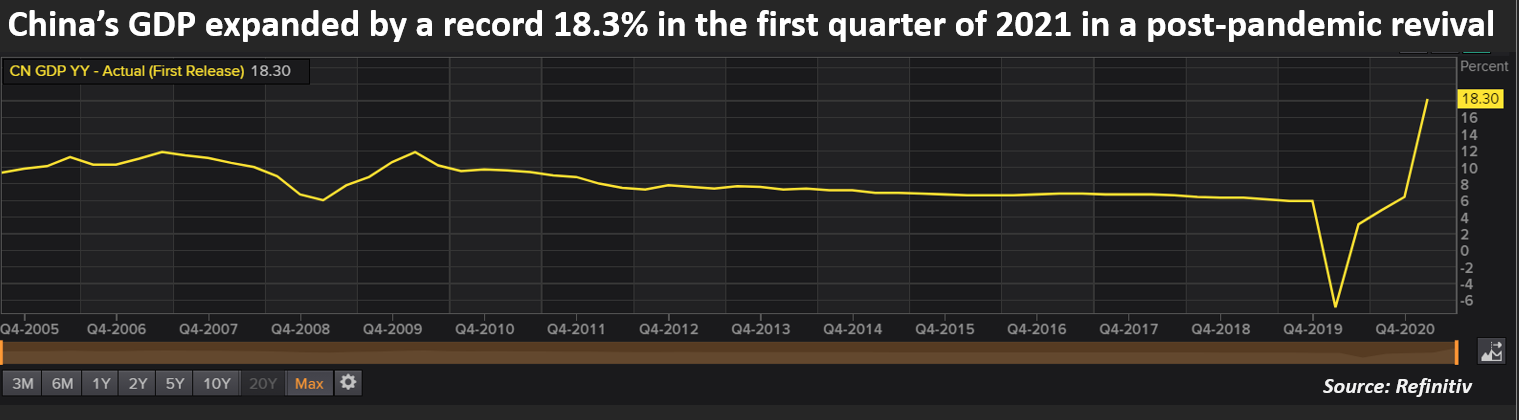

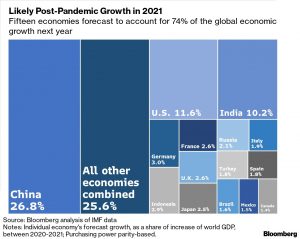

As economies around the world reeled from COVID related countermeasures, demand for made in China products soared. China posted a huge $535 billion trade surplus in 2020 according to the AP; a 3.6 percent increase in exports over 2019 to a total of $2.6 trillion; and a subsequent 1.1 percent reduction in imports. At the same time China overtook the US to become the EU’s top trading partner in goods, according to Eurostat data.

As a result of the asymmetry of global trade, shipping rates reached a 12 year high at the end of last year. Containers continued to flow out of China’s ports but the imbalance of trade with COVID affected countries meant that the containers simply were not returning in the same volume. This led to a sudden spike in freight rates and increased shipping delays. All this made the rail freight option very attractive in 2020.

At Horgas itself, three giant rail-mounted gantries rise from the desert and meticulously move up and down the lengths of freight trains arriving from China and load them onto trains waiting on Kazakh tracks all backed by a snow- capped mountain range. These giant cranes are needed to transship containers onto Kazakh trains and vice versa as Kazakh rail uses slightly wider – former Soviet – rail lines. In addition to the railway terminal a new highway crossing from China to Kazakhstan opened in November 2018.

According to Yu Chengzhong, Chairman of the Board, already 45 percent of the port’s cargo originates from outside Xinjiang. He explains how provinces closer to the sea are switching to the overland route; from oranges in Hunan, to consumer products in Zhenzhou.

The development of the dry port has been impressive: productivity at the port has rocketed in recent years and it now handles over 180,000 TEUs a year, Yu told Beijing Review. That figure is expected to rise to 500,000 TEUs by 2023.

“Before the port was built it would take three days to reach Astana in Kazakhstan, all on dirt roads,” Yu continued to explain, “but now it’s all express highway or rail freight so the time is just hours now.”

Although some eighty percent of the goods shipped through Horgas go to the countries of the former Soviet Union, and 35 to 40 percent go to Uzbekistan alone, on January 3rd 2017 the first Yiwu to London train departed carrying 44 containers via Moscow and Minsk arriving at London’s Barking Eurohub freight terminal. On April 10th that same year the first London to Yiwu train departed carrying 88 containers covering the 12,000 km journey in just 18 days compared with 40 days for sea freight.

Added to this, the Port at Horgas provides a train route – via Almaty and across central Asia – to Tehran, with the first cargo trains arriving from China in 2018 after completing the 10,400 km journey in just 14 days and giving China increased access to this energy rich region.

But development of the port has also been a driver for local industries in Xinjiang. And horticultural projects have sprung up in the Ili Region. Where once there was open grassland, vast fields of flowers bloom and fields of lavender stretch to the horizon.

But Horgas is not Xinjiang’s only trade route under development. Xinjiang’s oasis city of Kashgar has a history stretching back more than 2000 years and was a key trading post along the historical Silk Road. Now it is the start point of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), one of the biggest projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Over the course of decades roads have been built – with great hardship and many challenges given the formidable terrain – from Kashgar to Pakistan’s Gwadar Port allowing Chinese cargo to be transported overland to the port. Gwadar Port is located at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, just outside the Strait of Hormuz, with access to the key shipping routes in and out of the Gulf.

Gwadar Port is central to the CPEC, and a key component in the BRI. China Overseas Port Holding Company plans to expand the port, constructing nine, new multipurpose berths. Construction and operation of the port was awarded to China in 2013 and it gives China an alternative to potential choke points like the Straits of Malacca.

This huge level of investment in Xinjiang’s infrastructure is feeding back into local communities in many ways; presenting new business opportunities, opening new markets and helping facilitate China’s poverty alleviation campaign. Given Xinjiang’s strategic position and increased connectivity with Central Asia and the Eurasian landmass at large, the region is no longer a landlocked backwater; but becoming a land-linked logistics hub.