A version of this article appeared in Beijing Review magazine.

On Friday March 10th, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the 16th largest bank in the United States, became the second largest banking bankruptcy in US history. This was the third bank to collapse in week following New Republic and the crypto-focused Silvergate. In the wake of the announcements President Biden was quick to reassure depositors that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) would cover all deposits irrespective of the FDIC USD $250,000 ceiling.

The collapse of SVB is already creating ripples across the world. Bloomberg reported recently that Sweden’s largest private pension provider has a potential USD $2bn in exposure to banks linked to SVB and Forbes reported hundreds of Indian tech start-ups have been affected, to name but two. Added to this, there is reason to believe the crisis could become more serious than the 2007-9 financial crisis.

The first reason is the nature of the crisis. While the financial crisis of 2007-8 was caused by widespread corruption linked to the derivatives market for repackaged sub-prime mortgages that had been fraudulently valued the current crisis is systemic and was caused by overinvestment in Government issued debt or Treasury Bonds.

COVID-pandemic related measures in the US created a vast transfer of wealth upward in the US economy and this transfer materialised as huge deposits in the banking sector that banks invested in treasury bonds in order to profit from arbitrage. At the time, banks were paying around 0.2 percent interest on short-term deposits and were able to make upwards of 2 percent on treasury bonds.

However, this vast transfer of wealth, combined with the supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-pandemic and compounded by anti-Russia sanctions related to the conflict in Ukraine fuelled inflation across the West leading to wage rise demands that potentially threatened corporate profits and correspondingly stock prices.

In order to stop these wage demands and protect asset prices in the financial sector the Fed decided to increase unemployment by 2 million by raising interest rates. However, to do this the Fed had to issue new bonds at a higher rate of interest thereby reducing the value of the bonds held by the banking sector. This meant that the bonds held by the banks were no longer worth what the banks had paid for them.

Essentially this is a paper loss and everything would have been fine so long as no one needed their money in the next ten years. The problem came when depositor decided to move their deposits to money management funds based on the newly issued bonds that offered a much higher rate of interest. To cover these withdrawals the bank was forced to sell its treasuries and realise the losses on its balance sheet making it incapable of covering the deposits.

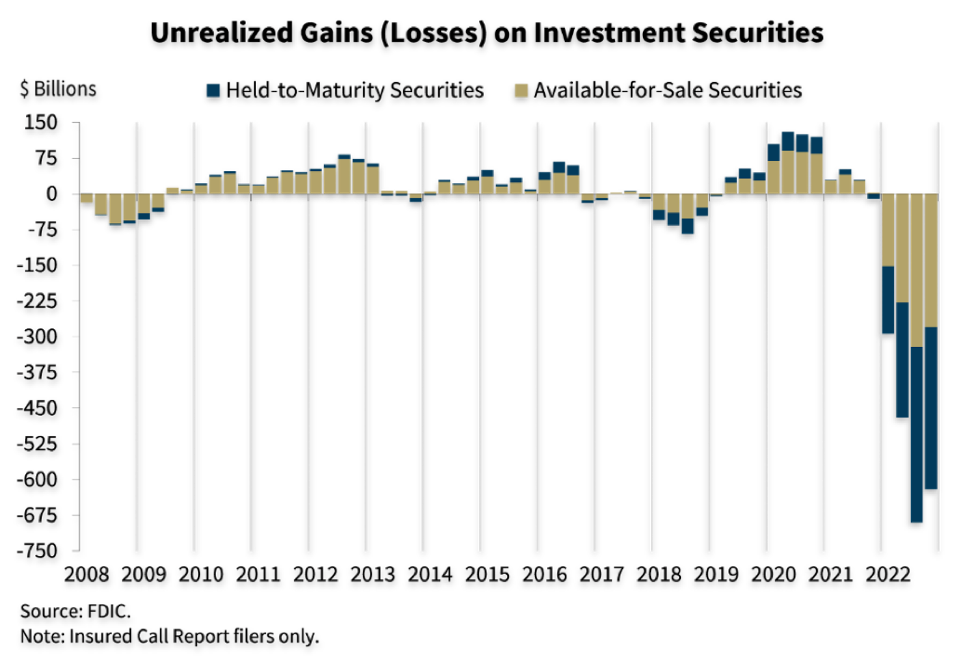

So, the question is: How big is the problem? Well, according to the FDIC, unrealized losses on investment securities across the banking sector are currently running at around USD $680bn. Although, this is not a small amount of money, it is relatively small compared to the totality of the derivative debacle of 2007-9 when the Fed bailout the banking sector to the tune of USD $700bn in taxpayer’s money and a subsequent USD $40 trillion in quantitative easing (QE) over the next 13 years.

President Biden, Treasury Secretary Yellen and Chairman of the Federal Reserve Powell were quick to try to calm markets. Biden announced the FDIC would cover all deposits even those over and above the legally mandated USD $250,000; Powell announced the collapse would not alter the Fed’s interest rate policy before quickly back-pedalling under pressure from the financial sector; and Yellen announced that the Fed would open a discount window allowing banks to borrow against the book value of their now underwater treasury investments.

This creates two immediate problems for the Fed. By guaranteeing deposits in banks deemed too important to fail they are potentially opening the door for runs on banks that are not too big to fail and by allowing banks to borrow against the book value of their assets – not the market value – they are potentially on the hook for USD $620bn.

It also means the Obama-era policy of quantitative easing has painted the Fed into a corner. In essence, QE has inflated asset prices – stocks, bonds and real estate – so much that any attempt to cool the economy and address inflation will have significantly negative consequences for the financial markets. It also can’t lower interest rates to reinflate asset prices without stoking inflation.

In essence, the Obama policy kicked the financial can down the road without addressing any of significant structural problems it illustrated. The most significant of these structural problems is the derivatives market which has ballooned since 2007.

Derivatives are basically bets on what will happen in the market and were first invented to help the agricultural sector hedge against unexpected changes in the price of inputs or outputs but grew massively in the era of near-zero interest rates when anyone could borrow money to go to the races.

When Warren Buffet famously labelled derivatives “financial weapons of mass destruction” in 2002 the ‘notional value’ – the value of the assets underlying the bets – of the derivatives market was estimated at USD $56 trillion. However, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) estimated the notional value of the derivatives market was USD $610 trillion at the end of June 2021. BIS estimate that figure could now be close to one quadrillion, many time larger than global GDP, but the real figure is hard to know because most of these trades are done privately.

Derivatives add a layer of financial risk to the economy because the market is so interconnected that failure by a counterparty can quickly have a domino effect and most of the banks involved are too big to fail.

According to Ellen Brown, founder of the Public Banking Institute; “[Derivatives] are sold as insurance against risk, which is passed off to the counterparty to the bet. But the risk is still there, and if the counterparty can’t pay, both parties lose. In “systemically important” situations, the government winds up footing the bill.”

As of the third quarter 2022, the federal bank regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, over 1000 federally insured financial institutions held derivatives but over 88 percent were held by five large banks: J.P. Morgan Chase ($54.3 trillion), Goldman Sachs ($51 trillion), Citibank ($46 trillion), Bank of America ($21.6 trillion), and Wells Fargo ($12.2 trillion). Increasingly it looks like Credit Suisse might have been the first domino to fall.

Worryingly, many of the bets in this market relate to interest rates which are now rising. Additionally, most of these bets are placed on assets upon which the purchaser has no underlying interest. As Brown points out, “If you don’t own the barn on which you are betting, the temptation is there to burn down the barn to get the insurance.”

References